SALVADOR SANCHEZ REMEMBERED

By Sean Sullivan

Salvador Sanchez is unquestionably one of the greatest fighters in boxing history. However, due to the brevity of his career, he is often forgotten about or overlooked by historians. But after reviewing his accomplishments, it is hard to deny that the former WBC featherweight titleholder from 1980-82 deserves recognition.

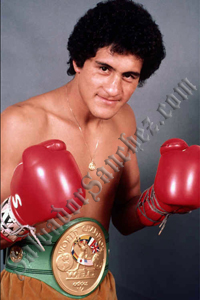

Salvador Sanchez promotional photo for his fight with Azumah Nelson

Within seven years as a pro, Sanchez amassed a 44-1-1 (32) record, but even more remarkable were his nine title defenses against top-notch opposition over a two-and-a-half year span. After defeating the fan-friendly brawler Danny “Little Red” Lopez for the title by 13th-round TKO in what was considered a big upset, Sanchez defended it against Ruben Castillo, 48-1 (26); Lopez in a rematch; the undefeated, 15-0 (10), freakishly tall at 6’1” Patrick Ford; the tough Juan LaPorte, who went on to become a champion; the number one contender and European champion, Roberto Castanon, 43-1 (24); the undefeated knockout artist, Wilfredo Gomez, 32-0-1 (32); Pat Cowdell; Jorge Garcia; and the future three-time champion, Azumah Nelson.

Sanchez broke barriers for lighter-weight fighters, earning millions of dollars. Sanchez’s title defense against Garcia was the first fight between two featherweights ever televised by HBO. To demonstrate just how highly respected Sanchez was as a fighter, he shared “Fighter of the Year” honors with Sugar Ray Leonard in 1981—the year Leonard knocked out Tommy Hearns. A popular figure both in and out of the ring, Sanchez also worked with salsa sensation Rubén Blades in May 1982, on a movie called “The Last Fight” (which was later dedicated to him after his premature death).

On Aug. 12, 1982, at the age of 23, Sanchez’s life was tragically cut short when he was killed in an automobile accident, while heading home from a night out with close friends alone in his Porsche 928S. Eerily, Sanchez often had premonitions of his own death. He would make comments with those very close to him about not living a long life and spoke about the way he wanted his funeral arranged. It was held in his hometown and over 50,000 people showed up to pay their respects to the fallen fighter.

Every year on the anniversary of his death, Sanchez’s hometown of Santiago Tianguistenco, Mexico, hosts a four-day celebration in honor of his life.

#

As a youngster, Sanchez was a fan of wrestling, which was very popular in Mexico, but his closest friend, José Sosa, brought him to a boxing gym and he soon fell in love with the sport. At the age of 13, Sanchez started fighting as an amateur, but he only had nine bouts, winning all of them, because he was eager to turn pro, which he did in 1975. Initially against their son’s choice of profession, Sanchez’s parents would eventually come around to accept his decision; and for every one of his fights, his mother taped a cross inside his shoes made from a palm branch, a Christian symbol of triumph.

Always well-conditioned, Sanchez ran eight to 10 miles in the mountains, six days a week. He liked to train at a ranch, with outdoor training facilities, even during the summer in the 90-100-degree heat. A member of his team, Dr. Valenzuela, helped perfect a method of his training so that Sanchez could spar five-minute rounds, then have his heart rate return to normal in 45-seconds of rest.

#

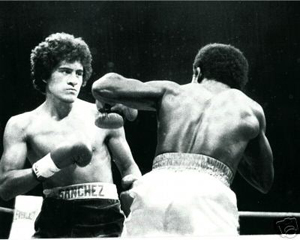

Salvador Sanchez avoids a left hook

After Sanchez halted Castanon in 10 rounds, negotiations began to set up a mega fight with knockout artist Wilfredo Gomez, who, to this day, is widely considered the best Puerto Rican boxer of all time. While the two victories over the exciting Lopez gained Sanchez fanfare, it was really the Gomez bout that made Sanchez a superstar.

Wanting to stay active, Sanchez took a tune-up non-title fight against Nicky Perez just five weeks before he was scheduled to face Gomez. By today’s standards, Perez, 50-3 (26), was no tune-up, but Sanchez won a 10-round decision with ease. After the verdict was announced, Gomez entered the ring and got into a little shoving match with Sanchez to help promote their fight.

Gomez was the only fighter Sanchez really had a personal grudge against. Before their heavily-hyped bout, Gomez often disrespected Sanchez personally and in public. Sanchez’s widow, Teresa, recalled that he told her, “I’m going to put a hurting on this guy,” and when the fight was over, Gomez was left with a fractured cheekbone and both eyes swollen shut. It appeared that Sanchez could have finished Gomez off sooner than he did in the eighth round, but perhaps wanted to extend the punishment he dished out.

Sanchez’s lone fight at Madison Square Garden, on July 21, 1982, would be the last fight of his career. Azumah Nelson, 13-0 (10), was a late replacement, brought in on two-weeks notice, when the original opponent, number one contender, Colombian Mario Miranda pulled out with an injury. Nelson was an unknown and not expected to give Sanchez much of a battle. It turned out to be the toughest fight of Sanchez’s career, but he was able to stop Nelson in the 15th round.

All-time featherweight great Willie Pep was in attendance that night and was impressed with Sanchez, saying, “I’m glad he wasn’t around in my era.”

Plans were underway to have Sanchez move up to lightweight to face Alexis Arguello, after a scheduled LaPorte rematch. According to Sanchez’s attorney, Juan Jose Torres Landa, who handled the pre-fight negotiations, Arguello, who had problems with movers, didn’t really want to face Sanchez, knowing he would have trouble with the Mexican’s style. The fight was in the signing stages but never got finalized. Had he gone on to fight Arguello, Sanchez intended to retire afterward and study to become a doctor.

The only blemishes on Sanchez’s record include a split decision loss and a draw, against Antonio Becerra and Juan Escobar respectively. After climbing off the canvas twice to escape with the draw in 1978, Sanchez changed his management and hired trainer Enrique Huerta, who helped transition him from being a brawler to a boxer-puncher.

#

Today, Sanchez’s mother, Maria Luisa, still lives in Santiago Tianguistenco, and runs a beauty salon with her daughter Paula. Teresa, who never remarried, is a school teacher and also has a clothing business. The house they owned remains in the exact same condition it was in when Salvador was alive, set up as a memorial. Their two sons are grown-up; Christian is a language expert/interpreter and Omar is a lawyer. However, the fortune Sanchez accrued throughout his boxing career mysteriously disappeared and his family was never able to benefit from it after his death. But since then, Grant Elvis Phillips, owner of the Grant Boxing equipment line, has gone out of his way to help the Sanchez family financially. Phillips is also the owner of the worldwide rights to the name and likeness of Salvador Sanchez and is working on putting together a museum with an extensive collection of Sanchez memorabilia. A movie and several exciting projects are in the planning stages as well.

Sanchez was properly inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1991.